By David

Whether the long term goal is to win a national title, get a university scholarship in the USA or win a major international event, every swimmer is entitled to dream big. The speed at which major goals are realized will vary from swimmer to swimmer but should never be constrained by coach, athlete or parent.

Having said that, an Olympic gold medal at 13 is probably a touch optimistic, although Amanda Beard did get close to even that lofty goal. Toni Jeffs is the fastest improver I have seen. When she came to my squad she was a consolation finalist in the New Zealand open nationals: about 10th in NZ. In just twenty-four weeks, she improved to New Zealand’s 100 and 50 freestyle champion and was placed 5th in the 100 freestyle and 4th in the 4×100 freestyle relay at the Auckland Commonwealth Games. Nichola Chellingworth had a similar stellar rise. She swam a NZ national 12 year old record in only her second ever competitive swimming race. Jane Copland qualified for the New Zealand Open Nationals when she was twelve years old. She made a top eight World Cup final in Hong Kong at 13.

These are unusual examples. But they do highlight the importance of not putting time limits on achieving goals. All three swimmers were encouraged to dream big, a quality that contributed hugely to their early success. A more normal story however is a swimmer I coached in the United States who had swum at a modest level for years when he came to my team. He took a further two years to swim in a USA national championship final. His progress in the first six months was modest indeed and he was a very talented man. Another talented swimmer I coached in Florida swam with me for eighteen months before she began to make progress. She now swims well in the United States National Championships and has a partial athletic scholarship to a good American University.

These examples got me thinking about the factors that influence the speed of a swimmer’s improvement. Talent is a factor but not an important one. Probably the biggest contributing difference between those that took time and the three rapid improvers is the history of their early careers. When the slower improvers came to my program they were damaged goods. Their careers needed to go through a rehabilitation period before they could progress again. For example one of the Florida swimmers was ranked 4th in the USA at twelve and had been exploited for years by a poor coach and an ambitious mother. The three rapid improvers came to my program with no such problems. Toni had been coached by her father who was a very good coach. Probably his only “crime” was not pushing his daughter hard enough. He certainly laid the foundation from which she could progress quickly to international success. The other two had never swum competitively before their early successes.

A second important factor is the emphasis a Lydiard program puts on the mileage swum in the buildup. Swimmers simply cannot expect the best racing results if their training buildup mileage is low. Some programmes try and compensate for lost mileage by increasing the severity of the anaerobic and speed training. That seldom works and is certainly not good for the athlete. For senior squad swimmers to progress to the sort of long term goals mentioned above requires 70 to 100 kilometers a week in the buildup. A characteristic common to the rapid improvers is that all three did many 100 kilometer weeks. The two slower improvers from Florida also swam similar distances. One of them had a best 10 week total of 950 kilometers. Swimmers who average 40 kilometers a week are just not providing themselves with a sufficient base to build a successful career. When Alison Wright was one of the world’s best middle distance runners she ran for a four year period and missed just three training sessions. I know swimmers who miss that number and more every week. Alison’s best ten week mileage was 1200 miles (1920 kilometers). Success is seldom by chance.

And finally take into account how well a swimmer is actually improving. A very good figure produced by the American Swim Coaches Association is their 3% annual rate of improvement target. If swimmers want to be international athletes or achieve one of the long term goals mentioned earlier in this article they should aim for an average improvement of 3% per annum. Duncan Laing told me Danyon Loader averaged 3%. Jane Copland averaged 2.8%. Dream big but keep in mind this American figure. When it comes to swimming they know what they are talking about.

Remember though that not every season will be an improvement over the previous season. When a pause occurs there is no reason for concern. Occasionally swimmers need time to consolidate. Two or three seasons of good progress go by and for no obvious reason there is a season where the swimmer seems to be drawing breath, gathering reserves and getting ready to go again. Certainly the careers of Toni, Nichola and Jane seemed to work that way. Improvement was not a series of neat 3.0% annual steps to national swimming honors. When a pause does occur, be patient. Take the long-term view. Because the method of training is sound, move on and it will come right.

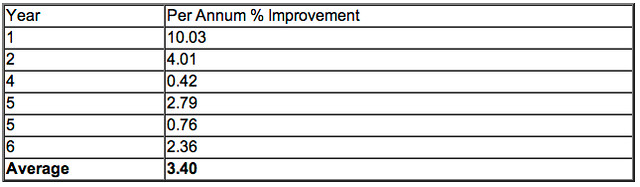

To illustrate the point, set out below is a table showing the percentage annual improvement in competition times for an international swimmer I coached from the age of 12 to 18. The data shows that after two early years of big improvements this swimmer went through a four year period of good improvements and plateaus; a trend quite common in developing swimmers.

So there it is; dream big and urgently but in evaluating your individual circumstances take into account your history; take into account how well you have done in the buildups; take into account how close you are to the 3% per annum rate of improvement. Only then will you have a balanced view of your current progress.